|

March 27, 2019 (Day 4,318)

Quick Fix: 36° 37.2 N / 29° 06.1 E

Conditions: Wind: Variable Sky: Clear

Where Are We Now?!

Transitions between countries and regions on Dream Time are, typically, slow and gradual ones - temperatures may shift with the latitudes, along with an easy adjustment through time zones. New cultures, too, are something we normally have plenty of time to research and prepare for. But when Dream Time was shipped from Thailand to Turkey we felt a little like James T. Kirk teleported from the comforts of his ship, only to suddenly find himself on a strange alien planet with odd creatures and a lot of questions. While Dream Time lounged as a guest on Annette through the Red Sea we teleported to Qatar, and it was, indeed, a strange and wonderful new land for us. One where curious camels roamed sandy paddocks, thobe-wearing-texting Arabs raced Bentleys across multiple lanes, and an immaculate new city of glass and stainless shimmered in the desert heat. We kite surfed, rock climbed and dune-bashed with our hosts Carol and Livia, and we felt right at home. Shukran dudes! |

|

|

|

|

Mar 26, 2019 | Fethiye, Turkey - SPLASH! Hello Dream Time, welcome to the Mediterranean! More to follow... |

|

Mar 24, 2019 | Fethiye, Turkey - Thailand jungles to snowy Turkish peaks! Dream Time's ETS (Estimated Time of Splash) - tomorrow 1900hrs. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

A Passage From The Past

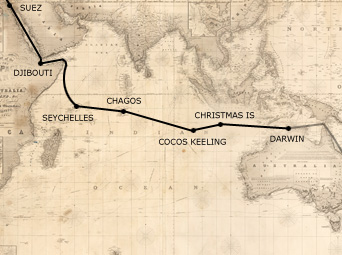

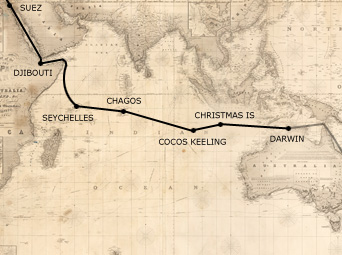

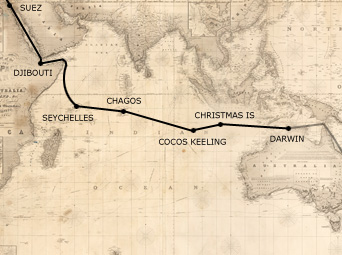

Australia to the Mediterranean Sea

An 11,267 nautical mile, five-month voyage on Aphrodite |

The following are original log entries, excerpts from my voyage on Aphrodite in 1994 from Australia to Italy. These entries, when combined with Dream Time's, will perhaps one day complete a circumnavigation - two wakes joined together to circle the world. After-all, without the inspiration from Aphrodite's voyage, Dream Time's journey would likely never have been realized.

Aphrodite's journey began in Sydney and ended successfully in Rome five months later. A noteworthy accomplishment considering Peter, the owner of Aphrodite - a handsome 42’ Lidgard cutter-rig sloop - had never crossed an ocean before, and it was only discovered during the course of the voyage that the ‘elite’ crew of five he had assembled had absolutely no meaningful experience to add.

Due to exciting conflicts in character, Aphrodite’s navigator was asked to leave the vessel in Darwin, the second navigator failed to show, and a third member of crew chose to disembark before setting sail across the Indian Ocean.

Within four weeks and before Aphrodite had even left Australia, Peter’s crew of five was reduced to just two. Only Lewis remained, a Sydney fireman, a man I am honored to call a true friend, and myself, who at 24 years of age took the responsibility of navigating the remaining 8,782 nautical miles - only because I knew no better.

While Dream Time is transported across the Indian Ocean, into the Red Sea and north to the Suez Canal, we hope you enjoy reading excerpts from the voyage that Aphrodite sailed.

Click Here for Entry 1 of 3 - Darwin to Cocos Keeling >

Click Here for Entry 2 of 3

- Cocos Keeling to Seychelles >

Click Here for Entry 3 of 3

- Seychelles to Suez Canal >

ENTRY 1 of 3:

Darwin - Christmas Island - Cocos Keeling

Darwin to Christmas Island - August 12th, 1994

12° 17.2’ S / 130° 35.0’ E

After all the preparations and anxiety, we finally left the giant continent of Australia behind us today. Watching the coastline disappear into the horizon we each said our silent farewells to loved ones and memories.

We’re running with the wind, catching every breath in our canvas, the sails are flared out like the wings of a giant swan. We have only the sea in front of us now, a feeling that none of us has experienced before. Every direction I look the sea is alive and moving, there is no land in sight and as the days go by we will sail further away from civilization. It feels like we are sailing into the wild, the deeper we go the more alone and vulnerable we will be.

The surface of the sea is a continuous movement of waves that have traveled for thousands of miles to greet us. The sunlight reflects off each crest making the world around us twinkle like a giant crumpled sheet of tin foil. The wind is blowing from the southeast, the waves are chasing us from behind as we sail to the west. Australia will shield and protect us for another few days then the waves will have time to build in size and strength, none of us knows what to expect. We each have a thousand different questions but are unable to answer a single one, only time will give us the answers.

The trade winds are blowing a steady fifteen knots and we’re averaging eight knots over the ground. I’ve set all the waypoints into the auto pilot and plotted our course west across the Indian Ocean - Christmas Island is our first stop, followed by Cocos Keeling, Chagos then the Seychelles before we head north to round the Horn of Africa. If the trade winds are kind we will see the extinct volcano of Christmas Island rise out of the ocean in ten days.

We haven’t spoken much about the journey ahead. Peter has not requested to see the waypoints I have programmed into the auto pilot nor the charts I am using to navigate to each island. I have suggested that whoever is on watch should take our position every hour, day or night. Although in the expanse of ocean this may seem excessive, we will be better able to determine our average speed and keep on course. In the early hours of the morning when the human body is at its lowest ebb, it is easy to forget about the dangers at sea. Anything to keep the person on watch focused is a good thing. We will not reef the main down tonight, the trade winds have been steady all day and the late afternoon sky is clear.

Darwin to Christmas Island: August 14th, 1994

11° 42.7’ S / 128° 29.5’ E

We have settled into the new routine with ease and have three hour shifts each to monitor our position and check for boats. Averaging one hundred and seventeen nautical miles a day, the trade winds have been unpredictable gusting up to twenty-three knots then dropping to ten. We’re all getting on extremely well and respect each other’s space, enjoying the freedom of being at sea and heading into the unknown.

We fill each day our own way. Peter spends much of his time writing to his family and rolling cigarettes, managing to spill much of the tobacco on the deck. Unable to afford large quantities of packet cigarettes, Peter has bought bags of tobacco and rolling papers. He has not quite mastered the art of rolling his own and often resorts to the help of a plastic gadget.

Lewis seems to enjoy spending his time reading, eating and staring out across the sea, something that you can never tire of. Each set of waves, each movement of the boat is different from the last. Relaxing into a state of meditation the sound of the ocean and the wind can hold you in a trance. It is quite easy to spend the entire afternoon just sitting on the deck doing nothing.

I start each day, regardless of my shift, the same way. I have found my dreams to be most unusual since the beginning of the journey. Most nights are filled with epic stories of adventure and mystery. I am lucky to be able to remember them and spend the first half hour of my morning watch sipping a mug of black coffee and writing in my dream diary, I have entitled “Dream Time.” The rest of my day I spend reading, writing, sketching on the calm days, whittling the pieces of drift wood I’ve gathered along the way and exercising. The latter is by no means easy on a boat at sea. I have devised a routine by utilizing parts of the yacht for dips, sit-ups, press-ups and a variety of different movements that will help to keep me in shape. Rolling around on the deck trying to perform my daily exercises, I provide the afternoon entertainment for Peter and Lewis.

Darwin to Christmas Island: August 15th, 1994

11° 24.7’ S / 126° 32.5’ E

With the security of Australian waters now far behind, we are sailing in the Timor Sea, sixty nautical miles south of Timor, Indonesia. Unauthorized boats are prohibited to enter the waters surrounding these islands. Unless you have a compulsory cruising permit, which we do not, yachts must stay out of this territory.

Catching so much wind from behind Aphrodite is pushed forward at a tremendous pace. Running with the wind can be a dangerous tack. With the wind directly behind the boat becomes unstable, with each gust the auto pilot fights constantly to keep our heading true. If the wind starts to blow above twenty-five knots we will take down the pole.

Assistance at any time of the day or night is only a shout away. If sails need to be reduced, changes are made at the exchange of a watch. If, however, it is urgent you will be wrenched from a peaceful sleep with a rough hand on your shoulder and a loud voice in your ear. Because of this impending interruption I find that I am always listening to the noise of the boat and am aware of the movements around me, even when asleep. If they should change suddenly I immediately awake to check on the situation, as does Lewis and Peter.

We have become a team of three and rely heavily on each other. Even if you are not on watch, you are never really off duty. Lewis has the watch before me, so he wakes me when I am on, I wake Peter as he has the watch after me. I know it’s time for my shift as I can hear Lewis thumping around on deck making his way down to my cabin to wake me.

Darwin to Christmas Island: August 21st, 1994

10° 32.2’ S / 108° 17.0’ E

Wanting to celebrate our approach to Christmas Island I baked some muffins today. Mixing flour, oil, water, eggs, salt, raisins and baking powder in a random order and guessing quantities I was surprised when it worked. Lewis ate his ration of seven muffins within three hours and is begging me to bake some more. We are out of bread, unless we can buy some in Christmas Island I have a feeling I will be baking a few loaves in the weeks ahead.

In helping me to keep my days full I have already planned the route to Fiumicino and estimated our arrival times at each port of call. I have taped these dates on the wall above the navigation table with the shift and cooking rota.

Christmas Island ETA August 24

Cocos Keeling ETA August 30

Chagos ETA September 16

Seychelles ETA September 30

Djibouti ETA October 18

Suez Canal ETA November 8

Fiumicino, Italy ETA November 25

Christmas Island: August 22nd, 1994

10° 23.2’ S / 105° 58.6’ E

I cannot remember a more beautiful evening. Christmas Island greeted us with a sunset that lasted only a few minutes but will burn in my memory for a lifetime. Never before have I felt such a sense of achievement as I do right now after navigating over 1,487 nautical miles of ocean.

Aphrodite is anchored only three boat lengths from the shore. We have decided to keep watch for the rest of the night to make sure the anchor is holding. If the anchor drags we would be on the rocks in less than twenty seconds. It is a strange feeling to be so close to land again after ten days of just ocean. The tall cliffs that almost completely surround the island reach up into the night and seem to touch the stars.

Lewis and Peter have gone to bed leaving me alone on my watch. Sitting in the dark, munching on crackers and sipping earl grey tea, the rocks behind me seem to be closer each time I turn to look at them. Your mind can play tricks on you when you are tired and in need of rest. The sound of the waves crashing on the rocks and the movement of the boat as it is thrown around by the rough swell is keeping me on edge. I am finding it hard to relax. Convinced we are closer to the shore now, than when we ad anchored two hours ago I have dropped a line with some diving weights on the end of it, I am able to judge by the angle of the line if we are dragging.

Christmas Island: August 24th, 1994

Christmas Island was first sighted in the seventeenth century and was later named on Christmas Day 1643. With a population of two thousand, the island’s industry is based around a phosphate mine which was first opened in the 1870’s. The phosphate is brought down the side of the island on a giant conveyor belt or on the only major road by trucks. The community is predominantly Chinese, Moslems and Malay with a few Australians.

The wind has been blowing hard at twenty-five knots all day, kicking up the dust from the island and covering Aphrodite. The tall cliffs reach up to almost a thousand feet above sea level. The tip of this extinct volcano is covered in vegetation and hosts several rare and endangered species. Sixty-three percent of the island has been declared a National Park. The most unusual feature of the wildlife are the Red Crabs (land crabs) that migrate annually from the upper plateau down to the shoreline to spawn and breed. Coming out of the heavy vegetation by the thousands they march to the shore covering everything in their path. Scurrying over buildings and roadways they storm the island like an army, lay their eggs then head back inland. Giant birds are constantly circling the island. Like vultures they seem to be waiting for one of the yachts to be swept into the cliffs by the swell. Using the trade winds that hit the tall cliffs they are carried high into the blue sky as far as the naked eye can see. Aside from the gantry and mine, Christmas Island is beautiful and sits alone in the middle of nowhere.

The sound of the Moslems call to prayer is broadcast across the harbor by loud speakers waking us up at five in the morning. Every few hours they gather in the Mosque by the harbor, face Mecca and pray. Sitting on the boat alone under the warm sun, listening to the call to prayer fills me with peace. In a way it is nice to have this time alone when Peter and Lewis are ashore.

With the charts laid out over the table I have plotted the waypoints across the stretch of ocean to Cocos Keeling, five hundred and thirty miles away, and programmed them into the auto pilot. In about five days we will reach the atoll which is the last Australian outpost before we head deeper into the Indian Ocean.

NOTE: Australian immigration would not allow me ashore in Christmas Island as I had overstayed my tourist visa and was temporarily banned from the country.

Christmas Island to Cocos Keeling: August 25th, 1994

10° 24.6’ S / 104° 31.6’ E

It’s 2300 and a strange eerie night. The moon has yet to show itself in the cloudless sky and everything around us seems grey. It’s as though the colors have been drained from the night, there is no contrast, even the stars seem to be quieter than usual and visibility is extremely poor. A quite hush has fallen over the ocean around us, we have wind in our sails but even the movement of Aphrodite and the noise of the bow slicing through the waves seem to be suppressed.

This is our first night back at sea after leaving Flying Fish Cove. We are all pleased to be on the road again and are looking forward to our next stop - Cocos Keeling. Except the beer (Peter purchased eight cases of out-of-date Emu beer for $3.50 each, or about sixteen cents a can!), supplies were expensive on Christmas Island as they are flown in from Australia, Peter and Lewis didn’t buy anything. Cocos Keeling apparently grow their own crops and are more reasonably priced. With no fresh fruit, vegetables or bread left our evening meals for the next four days will have to get a little more inventive.

Christmas Island to Cocos Keeling: August 27th, 1994

11° 49.5’ S / 97° 55.6’ E

It has been over two weeks since I last felt fresh water on my skin, I am craving a shower. Although after a deck shower I feel clean and refreshed the salt water doesn’t do a great job. The sea is almost as warm as the air temperature now, making the experience of washing outside not quite as refreshing as it was sailing around the colder waters of Australia.

Lewis has not shaved since we left Sydney over seven weeks ago and is proudly displaying a full black beard. With no hair on the top of his head and deep creases in his forehead he looks like a pirate. Lewis sits in the shade of the main sail wearing sweat pants, a long sleeve shirt, a hat that covers the back of his neck, dark sunglasses and a white t-shirt that he wraps around his face. He’s careful not to expose himself to the sun.

I shaved off my beard before we reached Christmas Island, after experimenting with a goatee and mustache I’ve decided I feel more comfortable clean shaven. Peter does not seem too concerned about his personal hygiene much to the despair of Lewis and I. Showering only occasionally he does not seem at all bothered by the smell that is maturing in his cabin. Smoking up to five cigarettes an hour you can often smell Peter before you can see him. In the evening on his watch, the smoke drifts down into the humid cabin making the air harder for Lewis to breath. I have a hatch above my bed and am able to open it a few inches on the calm nights to help circulate the air out. As the nights get warmer I may start to sleep on deck.

With another couple of days to Cocos we have all decided to treat ourselves to a freshwater shower on the boat, a luxury that is seldom allowed. Even being thrown around in the bathroom, stubbing my toe on the toilet and banging my knee on the door handle didn’t lessen the wonderful feeling of fresh water on my skin. The two minutes each that we were allowed soon disappeared like the soapy water down the drain.

The sea has picked up a little with gangs of dark clouds hanging around in the blue sky waiting for us to sail under them. These squalls can dump enough rain on Aphrodite for a 'free' shower. I have stored a bar of soap on the deck for such an opportunity.

Christmas Island to Cocos Keeling: August 28th, 1994

11° 52.7’ S / 97° 44.6’ E

What a rough night that was! It’s 1015 I haven’t slept since 0300, the beginning of the morning shift, what Lewis refers to as "the party shift." I didn’t want to miss the sunrise so I have stayed up after my watch and let Peter sleep in again. The seas were a little bigger than usual and it was the first time I actually felt I was in danger since Don left us. Not because of the large swell or the strengthening wind, but because I was almost hit in the head three times by flying fish. Landing on the deck all around me the dolphins must have been hungry last night. Concerned that I could lose an eye I kept my head low in the cockpit sipping my coffee and listening to them landing all around me. Six landed by my feet and when the sun rose in the morning I counted another eighteen on deck.

The genoa that I sewed up is not holding very well. The heavy canvas is rotting and all the stitches are just pulling through. Almost the entire length of the leech has now come loose. We will be anchored in Cocos Keeling by tomorrow morning, and will see if they can reinforce the sail there. We have furled half of the genoa in to reduce the stress on the stitching and to slow down our speed. We want to make sure that we arrive tomorrow morning in daylight.

Cocos Keeling: August 29th, 1994

Now this is more like it! We’re anchored by the yellow quarantine buoy and are waiting for customs and immigration to radio us back. It’s 1000 and a beautiful warm sunny morning. The islands in the atoll are surrounded by reef that provides a natural barrier, keeping the strong currents and swell out of the lagoon. The water inside the atoll is calm, shallow and crystal clear, like a giant bath tub in the middle of the ocean.

The atoll was formed thousands of years ago by a volcano that was taken back by the sea. The submerged mountain rises up from the ocean bed forming a ring of islands, inside the crater the water is shallow and warm. We can easily see through the turquoise waters to the sandy bottom just twelve feet below. A variety of colorful fish and two baby white reef sharks have already come over to welcome us to paradise.

Cocos Keeling was first sighted in 1609 by Captain William Keeling. With a population of only five hundred and fifty, the islanders produce their own cash crops. With just one hundred white people living on Cocos the majority of the population are Malays. Most of the low twenty seven coral islands are uninhabited. With the majority of the Malay community on Home Island which is on the east side of the atoll, the international airport, hospital, quarantine station and shops can be found on West island. A ferry shoots across the six mile stretch of shallow waters to join the islands together.

The immigration officer has just radioed to tell us that he cannot come over until tomorrow morning but has given us permission to anchor with the eight other yachts making it very clear that we are not to have any contact with them until tomorrow. With Buffalo Soldier player on the CD we are sprawled out on the deck enjoying the peaceful movement of the boat for the first time in seventeen days. We are all in great form, drinking Emu beer and cooking steak on the barbecue chatting about the journey so far and all the great things to come. By the end of the night we were all merrily drunk.

Even with our differences the three of us were still getting along. Knowing each other for only two months we have shared a lot together. The trust we have in each other has seen us over three and a half thousand miles and I am sure it would see us through the next seven.

Cocos Keeling: September 3rd, 1994

We are still anchored at Cocos Keeling waiting for the sail to be mended and the diesel fuel we have ordered. The weather has taken a turn for the worse. The clear blue sky that was unbroken yesterday is now a low laying blanket of grey clouds that seem to touch the top of the masts. The water that was a transparent turquoise blue is now dark green and covered in little choppy waves. A white breaking wall surrounds the atoll where the giant swell is beating against the reef. Last night all we could hear was the relentless pounding of the breaking waves. Out of this chaos, motoring into the reef we were joined by a wind-beaten yacht early this morning. They reported that the wind was blowing over thirty knots and the rolling swell we experienced had turned into mountains of angry sea. They had to heave-to because the conditions were so severe.

I gave Lewis the charts and asked him to make photocopies on his next visit to the island. He rolled his eyes and said that I was lucky to be stuck on the boat. With only a small copier in the yacht club each chart would require up to ten separate sheets of paper and would have to be carefully tiled back together again. If overlapped by just a sixteenth of an inch a small island or reef could potentially be covered which could lead to disaster. I asked Lewis to take great care with each copy as every inch of the chart was important to us.

Lewis and Peter are going to a party tonight on the beach with the others yachties. I have a lot of work still to do with the charts that Lewis brought back this afternoon in a pile of over sixty sheets, at least it will keep me busy.

I’ve been in a foul mood for most of the day. We will be leaving as soon as the sail is mended and the weather clears. The thought of being stuck on Aphrodite for another two weeks sailing to Chagos is making me bad tempered. It will be a month by the time we reach the Salomon Islands and I will not have felt dry land under my feet. I’ve got “yacht” fever.

Cocos Keeling: September 5th, 1994

Peter and Lewis have gone to pick up supplies and the genoa from West Island. I am only allowed on Direction Island so have managed to avoid the chores of gathering water, diesel and food. I have plotted our next course to Chagos over fifteen hundred miles away, this is our longest leg across the Indian Ocean and will take us around two weeks.

The collection of atolls lie between the fifth and eighth parallel south of the equator. Diego Garcia is the largest island in Chagos Archipelagoes and is strictly off limits to yachts. The island has been made available to the United States military as a defense post and may only be approached in a serious emergency. The other fifty-five islands are all uninhabited and are patrolled by British customs. The Salomon atoll is north of Diego Garcia. With a sheltered anchorage inside the lagoon it is the most convenient for our passage west. Permission to anchor up to three months is allowed by the authorities. A fee of $55 is the only charge, no visa is required.

It’s funny how quickly we adapt to the environment around us. We have been anchored in Cocos for six days and have settled in to a comfortable routine. The thought of sailing into the middle of the Indian Ocean tomorrow fills me with uncertainty and apprehension all over again. We will raise the anchor after sunrise tomorrow and leave the friends we have made here behind, sailing alone to Chagos as the other yachts head to Mauritius.

NOTE: The immigration officers in Cocos Keeling initially denied me permission to go ashore. I had spent over three weeks without feeling land and was grappling with the very real possibility of another two weeks at sea before reaching the islands of Chagos. Thankfully, due to a storm and the generosity of a senior official, Aphrodite’s departure from Cocos was delayed and I was finally allowed to step foot on Direction Island. |

| |

|

|

|

|

A Passage From The Past - Part 2

Australia to the Mediterranean Sea

An 11,267 nautical mile, five-month voyage on Aphrodite |

ENTRY 2 of 3:

Cocos Keeling - Chagos - Seychelles

Cocos Keeling to Chagos: September 6th, 1994

11° 51.1’ S / 96° 03.7’ E

We left Cocos Keeling at 0700 with the morning sun casting long shadows across the empty beach. When we cleared Direction Island we raised our sails for the first time in a week and headed west with the sun rays. Lewis went below to kill the engine and we sat in silence, listening to the harmonic groans and creaks of Aphrodite coming back to life again after seven days of rest. It didn’t take her long to warm up and stretch her wings. Both sails were raised high and the fifteen knot breeze soon pushed us over the horizon.

We’re only fifty miles from Cocos but already feel a world away, consumed by the wind, the ocean and the skies. The Salomon Islands are over fifteen hundred miles away. To keep our cross track error down I have plotted each waypoint only one hundred miles apart. An alarm sounds each time one is reached, the auto pilot then needs to be directed to the next. We have fifteen waypoints set until Chagos.

The genoa is full of wind and holding well against the fifteen knot breeze. The sail repairer did a good job and stitched a length of red material down the entire leech to support the rotting canvas. When the sail is furled around the stay it looks like a giant forty foot candy cane hanging from the top of the mast. It’s not the most aesthetically appealing repair job I’ve seen, but as long as it holds up that’s all that matters.

The fresh fruit and vegetables we bought in Cocos have been rationed three ways. We have four tomatoes, a cabbage, three bananas and two oranges each for the next 2,580 nautical miles - one month! The bananas are already starting to spoil and will need to be eaten in the next day, the tomatoes, if kept in the dark should last a week or two. The cabbages and oranges have a longer shelf life and if rationed properly should see us to Chagos. There are no markets in Chagos, the islands are uninhabited, so it’ll be another ten days until we reach the Seychelles and can stock up supplies. Never again will I take fresh produce for granted.

Peter is looking much healthier than when I first met him in Sydney three months ago. Perhaps, away from the stress of running his business and the temptations of chocolate and other sweets, the diet of mainly pasta, as much as he complains about it, seems to be agreeing with him. The long hot days and the constant motion of Aphrodite are slowly burning the fat from his body. He looks as though he has lost at least ten to fifteen pounds.

He smokes endlessly, however, and spends the first couple of minutes before his early morning watch hacking and coughing. His endless chain smoking is really beginning to piss off Lewis, already they have had a number of arguments about Peter’s personal hygiene. It is a recurring problem between the two of them. Although I am just as frustrated by Peter’s lack of cleanliness I have been unwontedly given the role as mediator.

11° 22.3’ S / 94° 13.5’ E

Cocos Keeling to Chagos: September 7th, 1994

Rain all day. The wind has been steadily blowing harder peaking at twenty-seven knots and constantly changing direction. The waves seem even more confused now than they did yesterday. We’re making good time but the ride is rough. I managed to have a fresh water shower during one of the heavier squalls but considered wearing my harness. With soapy feet on a wet deck I was sliding all over the place, it wasn’t a pretty sight. Peter and Lewis looked on from where they sat in the cockpit, sipping coffee and watching me dance around on deck. Twice I almost fell overboard when Aphrodite was hit with a combination of waves, still my skin feels better for it.

We have made it a rule that a harness must be worn on the night watches at all times. With bigger seas, stumbling over the railing and falling into the empty ocean, far from the shipping lanes would mean certain death. Searching for someone in the night, not knowing when they fell overboard is a terrifying thought.

The temperature is getting hotter as we head towards the equator. It’s eighty degrees and humid with grey skies filled with heavy squalls. The sea is black as ink with only the white horses dancing atop each wave to distinguish the coming swell. There are a few windows in the clouds showing the stars, otherwise the skies are low and menacing. I only have another hour on my shift before I wake Peter at 0300. He served up beans on toast tonight, I’m dreading going into his cabin to wake him.

11° 08.7’ S / 91° 54.2’ E

Cocos Keeling to Chagos: September 9th, 1994

The skies have cleared and with it the wind. The sea is like a millpond without a ripple to disturb the glassy surface. We have been motoring for the last eight hours to make headway. It is hard to believe that everything in the middle of the ocean can be so calm. The opposing winds of the northern and southern hemisphere meet at the equator and cancel each other out, leaving a region of light or no wind known as the doldrums.

It is the perfect day to catch up on chores and to tidy the boat after three days of rough seas. The air is heavy and moist turning the cabin into a giant steam room. We have decided to air everything out by bringing the cushions, sheets and pillows up on deck. I spent a couple of hours in the morning washing the clothes and towels I have used over the last few weeks. Using sea water and a little washing powder we do our laundry in the same bucket we shower with. All my clothes are so dried out and saturated with salt I can practically stand them up on deck. They have not been washed in fresh water for four weeks, it’ll be another three at least before we reach the Seychelles and I will have the luxury of putting them in a washing machine.

I have not stopped sweating all day. Even in the shade it must be well over ninety degrees. With no wind blowing over the water the heat hangs in the air, squeezing the water from our bodies. I should drink more, but the water in the tanks tastes stale and is not very refreshing. It is only bearable if I mix a few drops of lemon juice with each glass. Peter and Lewis are both laying down in the cockpit, too tired to talk or argue.

The constant hammering of the diesel engine is driving us all mad. We have at least another week and a half before we reach Chagos. At times I wonder if we will make it before killing each other.

09° 58.6’ S / 89° 14.5’ E

Cocos Keeling to Chagos: September 10th, 1994

The wind has picked up enough for us to kill the engine but is swinging ninety degrees in seconds with no warning. Influenced by the dark squalls that are bruising the sky and spread to the horizon, the sails struggling to catch the unpredictable rush of wind and flap noisily each time a squall passes. We can only sit on deck and wait for the next squall to hit us, it would be impossible for us to avoid them. We have to take what’s coming and hope the wind will not be too severe.

The dark patches of water silently sweeping across the ocean surface indicate the coming wind. Watching the invisible force driving down on us we are able to judge the length of the wind and estimate its force. We only have part of the main up and have furled the genoa to form half a candy cane. Our speed varies from six knots to two. We want to save as much fuel as possible and will only use the engine if the wind dies all together. Frustrated by the conditions and each other we spend the days doing our own thing. The relentless crashing of the sails and constant rocking of Aphrodite as she is hit then released by each squall is worse than the thumping engine, we’re all tense and short tempered and have retreated into our own worlds.

07° 50.0’ S / 81° 36.0’ E

Cocos Keeling to Chagos: September 12th, 1994

The last couple of days have almost put us back on schedule. The wind has been picked up to twenty-five knots and with it so has our spirits. Aphrodite’s been crashing through the swell and the sails have been in need of constant trimming keeping us busy and off each other’s back. The skies are bright blue and clear of squalls. The only clouds are on the horizon that we are never able to reach. We went one hundred and forty-nine miles yesterday, close to our record in a twenty-four hour period. The water temperature is eighty-two degrees Fahrenheit, only nine degrees lower than the air temperature. The entire deck is wet from the waves that keep breaking over the bow.

06° 05.7’ S / 74° 57.4’ E

Cocos Keeling to Chagos: September 16th, 1994

No two days on this leg have been the same. The conditions vary from minute to minute and with them so do our attitudes. The wind has died down leaving us only one hundred and eighty miles from Chagos, but days away.

Our supplies are getting low, each day it seems we are exhausting another food group, today we ran out of cordial and potatoes and have used up the last of my muesli. The cupboards that were full when we left Darwin are now more than half empty, there are just a few tins left to roll back and forth with the swell, we have used sixty percent of our diesel and still have over twelve hundred miles to go. We could motor through the last two waypoints but it would leave us with very little fuel for the stretch of ocean to the Seychelles, without fuel it would be practically impossible to sail into the enclosed marina at Mahé.

We are all uptight again as it feels we are not making any progress, our morale drops with the wind and we are left drifting and bad tempered, Lewis and Peter have both spoken to me about the other. Lewis finds Peter’s attitude and habits narrow minded and annoying, while Peter says Lewis is stubborn and difficult.

Chagos: September 19th, 1994

The loom of the sun is beginning to take over the night. The glow from the east has spread across the sky chasing the darkness further west. As the light cast across the ocean the low laying Salomon Islands showed themselves for the first time only a few miles off our bow.

At a heading of 172O we entered the atoll under motor. We will be anchoring by Île Takamaka on the eastern side of the atoll four miles away. It’s ninety degrees Fahrenheit with only a few wispy cirrus clouds high above us to mark the blue sky. Like a private pool the water inside the lagoon is calm and eighty-six degrees. Lewis was watching for coral heads by standing on the bow railing peering down into the clear water. I have been scanning the ten islands circling us for signs of other yachts, but we are the only people here.

Dropping anchor off the sandy beach I have never imagined anywhere as beautiful. So far from mainland, Chagos Archipelago is out of reach from the ruinous hands of tourism. With no population to rely on tourist dollars, these islands sit unnoticed by the world. As soon as the anchor had been fastened Lewis and I were busy pumping up the inflatable to go ashore. Looking up every now and then to check the islands were still there, it was like a dream and we both wanted to touch it before we would wake.

After two long weeks of being surrounded by water these islands were like a mirage, we were craving land, the reverse of what you would normally see in a desert. With no harbor master, immigration or quarantine officers to clear us, we wasted no time and sped across the one hundred feet of water to Île Takamaka. Peter insisted that he wanted to stay on the boat in case the anchor dragged and would go ashore later. We were jubilant to be on land again, I was craving it more than Lewis after only two days on Direction Island. As happy as we were to experience it together we both soon went our own ways.

I have decided to sleep outside tonight as it is still well over ninety degrees in the cabin. Arranging my blankets and pillows in the ‘beer garden’ I lay naked on the deck looking up into the clear sky counting the shooting stars that seemed to be endlessly whizzing through space. It is nights like these I miss Catherine the most. When you can share special moments with someone you love, somehow it makes the experience more remarkable.

NOTE: British Marines patrolling the islands invited us to a beach barbeque so we remained in the Salomon Islands another two days. As a parting gift the marines donated fifty burgers, forty sausages, some fluffy buns and a bag of fresh fruit!

05° 14.0’ S / 70° 39.1’ E

Chagos to Seychelles: September 22nd, 1994

We have sailed right off the edge of the tiny Salomon Islands chart and have again returned to the Indian Ocean. Once in pristine condition this giant chart is now like one of my old schoolbooks - dog eared and covered in pencil marks. Each dot of lead that makes a trail from east to west tells a story. Like Morse Code, the dots and dashes are a reminder of the passages we have sailed. The scale of the chart is so huge that the dots practically sit on top of one other. The dull pencil lead markings each cover an area of a couple of square miles.

Returning to the larger chart is like stepping back from a situation and seeing it for what it really is. When you use the smaller more detailed charts it is easy to forget where you are, you become focused only on the immediate and can lose sight of the big picture. Looking at a tiny spec of pencil lead in the middle of a huge folding sheet of paper makes you realize just how small and vulnerable you really are. It is very gratifying to see the little pencil dots trailing across the sheet. Each dot represents another tiny goal reached, the islands we sail to are the immediate goals, and the chart I pull out every now and then of the west coast of Italy is the ultimate goal. This chart is still in pristine condition, it has never been used before. It still seems so far away I can’t ever imagine using it.

Just by looking at the coordinates marked across the Indian Ocean you can figure out who was on watch. Peter puts down more of a scribble than a dot, like he’s filling in a multiple choice box. Lewis uses the bow divider to mark our latitude and longitude, managing to spear the paper along the way. I use the parallel ruler drawing lines vertical and horizontal lines to mark our position. Navigating across the Indian Ocean isn’t particularly difficult. The real test will be transiting the Red Sea.

05° 17.0’ S / 67° 56.2’ E

Chagos to Seychelles: September 25th, 1994

The sky this afternoon was consumed by a giant squall that floated silently across the blue sky and as luck would have it right over Aphrodite. The clouds were dark purple and black like an angry bruise, we couldn’t run from it, only sit, watch and wait to see how bad the winds were going to be. Moments before it struck I suggested we reef the main, lucky really, because only seconds later the wind was over thirty knots.

The weather has been unpredictable all day, swinging completely around the compass between lulls. Only the heat remains consistent. The mercury is touching one hundred degrees and I have spent the last two nights sleeping on deck in the evening. Our spirits are low and the Indian Ocean seems bigger than it has ever felt before.

Peter is keeping himself busy, trying not to worry about the little fuel we have left in the tanks and the nine hundred miles of empty ocean to the Seychelles. Lewis is keeping to himself, and I feel rundown.

05° 17.6’ S / 67° 45.3’ E

Chagos to Seychelles: September 26th, 1994

We feel alone, as we have not sighted or had contact with another yachtie since Cocos Keeling twenty days ago, it doesn’t feel right. The only sign of human existence was a river of trash we potted floating in the currents of the ocean around one hundred feet wide. Everything from soccer balls, plastic containers of different sizes, oil drums to great tree trunks were caught in the drift. We had to change our heading a few times otherwise the debris would have crashed into the hull. God only knows where it all came from or where it’ll end up.

05° 37.1’ S / 64° 35.7’ E

Chagos to Seychelles: September 29th, 1994

Absurdly the clocks go back an hour today. Winding the hand back on my dive watch seems ridiculous to me. Nowhere has time mattered less, time is only measured now by the distance we’ve covered. I think it is Saturday, it feels like a Saturday, but I am only guessing. The days are becoming increasingly difficult to distinguish one from the next. The morning sunrises and the evening sunsets seem to come and go, only mealtimes and watches break the monotony of time. I do have an extra hour on my shift though, I wasn’t planning on going anywhere so it doesn’t really matter. I am thankful for the twelve coconuts I have stashed in the hull for carving, without them I do not know what I would do all day, I think that is part of the reason Lewis and Peter are not getting on very well, they have too much time on their hands to argue.

The alarm has been going off all night as there is not enough wind to even make a single knot. If Aphrodite stops moving, the auto pilot is unable to steer as there is no resistance on the rudder and emits a high pitched beep as a warning. We only have sixty liters of diesel left and another seventy for emergencies. We are cursing ourselves for not thinking of asking the British Marines for some diesel back in Chagos. For the time being we are drifting and have had enough. The days are so hot I am training at night during my watches, it helps the three hours go by faster and keeps me awake.

05° 44.0’ S / 56° 12.2’ E

Chagos to Seychelles: October 3rd, 1994

We have only one hundred miles to go. Our arrival in the Seychelles will mark the end of our passage across the Indian Ocean and the beginning of our journey north towards the Mediterranean Sea. We had radio contact earlier with a yacht from the Seychelles fishing around the reef who warned us of the one hundred dollars a day harbor fee. If he’s right we will only be staying a couple of days to refuel before we head out. Let’s hope he’s wrong because we all need some time away from Aphrodite, and each other.

05° 44.0’ S / 56° 12.2’ E

Chagos to Seychelles: October 3rd, 1994

It’s Monday morning, October 3rd, 1994. We have another four hours before we will step on dry land, but we can already see the reputed site of the Garden of Eden framed by blue sky in front of us.

I have been up for most of the night. My watch was from 0300-0600 but I was too excited to sleep and decided to stay up with Peter as we approached the island to keep him company. There are numerous boats of all shapes and sizes around the islands, most of them fishing. A motor vessel full of tourists cut across our bow, and an airplane seemed to land right in the harbor as it disappeared out of sight behind the mountains. I think Adam and Eve would be most upset if they could see their paradise on earth now.

Although the tourist industry is said to be kept under control to preserve the unique wildlife and unspoiled forests of these islands, it’s hard to imagine, surrounded by so many people, that it hasn’t had a destructive effect. Maybe I’m just not used to civilization after fifty-one days of relative seclusion.

Peter is going through his usual pre-authority jitters. Drinking his Emu beers he seems nervous waiting for the harbor master to guide us into the quarantine area. We had a little difficulty figuring out where we were supposed to go. After three attempts we were told to stay where we were, they we sending someone out to get us!

When the immigration and customs officers came aboard wearing clean pressed uniforms buttoned to the neck we knew they meant business. Their white starched shirts stood out in contrast to their dark jackets and even darker skin, these were African men. Unlike the Marines in Chagos, we felt that offering a beer to these chaps may not be considered proper and decided a soda or water would be more appropriate.

We sat around the table in the saloon going over passports, the ships documents and crew lists. Peter was having a difficult time filling out the forms that the officers were piling up for him to sign and complete. His hands were shaking to the point where you were unable to read his writing. The officers kept asking him to translate his scribbles, which only made him more nervous and his writing more erratic. Finally Peter gave up, unceremoniously made me captain of Aphrodite, and asked me to complete the documents before retiring to the cockpit for some fresh air and a cigarette to calm his nerves.

The Seychelles, Mahé: October 4th, 1994

Lewis and I set off today to find some local produce. The market was set up in a dirt clearing off the side of the road. Wooden tables were piled high with mounds of cabbages, lettuce, cucumbers and other green vegetables that spilled over onto the dusty floor. One table was covered in blood and giant fish heads. The flies liked this table the most and a black cloud seem to hover over it like a rain squall. Trying to feed off the congealed blood and entrails left on the stained table, the flies fought over each other and the palm tree leaves that swatted them away every few seconds. The dry air was saturated with hundreds of different scents. Vegetables, herbs, spices, teas, blood and the unmistakable stench of rotting food all mingled together to fill the enclosed area.

It was already dark by the time Lewis and I arrived back at the yacht club. On the third call we managed to get Peter on the VHF radio on channel sixteen and asked him to collect us from the jetty. By the look of him when he collected us it was obvious that he had already drank his way through most of the last Emu beers. He seemed upset that we had asked him to collect us and wanted to make it a rule that if we got back after a certain time he would not be responsible for collecting us. “Peter, it’s only eight o’clock, what’s the problem?” I asked. “I just feel as though I am the one that is always making the effort, and I’m fed up with it!”

The Seychelles, Mahé: October 7th, 1994

The more time Lewis and I spend together the better we seem to get on, quite the opposite to Peter. Peter is a good man but he is just so different from Lewis and me, it is hard work spending any great amount of time with him.

I returned to the boat to see if Peter needed a hand with anything while Lewis decided to spend the rest of the day by himself. Peter was upset with Lewis for wandering off and complained to me about him for the rest of the afternoon.

The Seychelles, Mahé - October 8th, 1994

All the cupboards are loaded with fresh supplies and the water and fuel tanks full to the brim, we are set to go. With final clearance we motored out of the marina and joined half a dozen fishing boats heading to sea, we were the only one bound for Djibouti.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

A Passage From The Past - Part 3

Australia to the Mediterranean Sea

An 11,267 nautical mile, five-month voyage on Aphrodite |

ENTRY 3 of 3:

Seychelles - Djibouti - Suez Canal

Seychelles to Djibouti: October 9th, 1994

03° 37.4’ S / 55° 21.1’ E

This is the longest leg on our journey. Over sixteen hundred miles away, around the Horn of Africa, nestled at the very western end of the Gulf of Aden, is Djibouti. This passage will take us out of the Indian Ocean and into new and unpredictable waters. Over the last six weeks we have all come to know the Indian Ocean well, apart from the days of unsettled wind, she has been good to us, the trade winds have been fair and the sailing conditions almost perfect. Our first ocean crossing experience has been a success. Leaving her waters behind and venturing into the new is making me unsettled and nervous.

Every sea has its own personality and reputation. With careful planning the Indian Ocean offers steady trade winds and ideal cruising conditions. The Gulf of Aden, although almost five hundred miles in length will feel like a harbor after the last seven weeks in the expanse of ocean. The one thousand three hundred miles of Red Sea to Port Suez will undoubtedly be the most challenging leg of our entire journey, we are prepared for the worst. Reaching the Mediterranean after battling against the northerly winds of the Red Sea will make the final twelve hundred miles to Italy a time to relax and wind down. Although the Mediterranean has a reputation of blowing hard or not at all, being so close to our final destination will make it feel like the journey is over.

We have been lucky so far, but I am sensing somewhere along the way we will have to pay for our good fortune and suffer just a little. It seems the further along this journey we travel the harder and more challenging everything is becoming, we will need to rely on each other more than ever before. The cyclone that has been building strength two hundred miles south of us is making me anxious and we only have another couple of weeks before the northwest monsoon prevails. It is important we are in the Gulf of Aden before the wind changes, but we have the doldrums to contend with first.

We have anticipated sailing through this dead zone and have filled our diesel tanks to the brim, the last thing we want to do is motor up the coast of Africa but we don’t have the luxury of time and need to press on.

Seychelles to Djibouti: October 10th, 1994

02° 15.1’ S / 55° 17.4’ E

We’re averaging three to four knots in a six to ten knot breeze. The spinnaker is holding well and ballooning out in front of Aphrodite leading the way. We’re still heading northwest as it’s important that we take advantage of the Somali current that runs up the coast of Africa. Crossing the equator at 51° 00’ and catching the current, that may reach speeds of up to seven knots near Socatra Island, will help us to round Somalia and enter the Gulf before the new monsoon begins. Some yachts have recorded up to one hundred and seventy miles in a day with the current under their keel.

The dolphins swam with me during my watch tonight. They are becoming like old friends, I was happy to see them. For half an hour they surfed off our bow waves that pushed them in front of Aphrodite. Swimming under my feet they looked up at me with grinning faces, whistling and chirping as if trying to tell me something, they seemed happy to see me too.

Seychelles to Djibouti: October 11th, 1994

00° 55.2’ S / 52° 20.7’ E

We have had the spinnaker up solidly for the last two days. The six knot breeze is like a whisper across the ocean but has been consistent in helping us average three to four knots. We are just a stone’s throw away from the equator, if the winds stays with us we will crossover late tonight or early tomorrow morning.

Lewis is brewing up another unique concoction for supper. He’s mixing in a whole variety of spices and herbs into the tomato sauce. Peter has just finished yelling at him as he felt it was disgusting not only because Lewis was mixing so many ingredients, but that he was tasting the sauce off the same spoon he was using for stirring. Lewis argued that the bubbling sauce would kill any germs and told Peter to lighten up. Peter whilst smoking, farting and generally oozing unpleasant odors from every pore continued to complain that it was not sanitary for Lewis to eat off the same spoon. I found it all rather ironic and couldn’t help smiling to myself listening to the two of them argue like an old married couple.

Seychelles to Djibouti: October 13th, 1994

00° 38.3’ N / 50° 41.0’ E

We’ve made it to the top half of the world! We crossed over to the northern hemisphere at 2055 last night. Our nose is pointing due north for the first time since we sailed up the east coast of Australia. We are racing to find the Somali current we have read so much about. It’s only 1000 and already we have had a gift from King Neptune, a beautiful thirty pound Tuna. We have fresh muffins baking in the gimbal stove for a celebratory snack, and now fresh fish for lunch. Tonight I will bake a pizza and we will all wash it down with a few glasses of wine. Not a bad first day in the northern world.

It’s ninety-seven degrees with only a light wind blowing at four knots from the southwest to cool the tropical air. The surface of the ocean is rolling and gentle, lifting up and down like the chest of a sleeping giant. Although the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) otherwise known as the doldrums, has a reputation for long calms, the region of no wind depends upon where you are crossing the equator and the time of year.

The charts indicate that an area of around three hundred miles may be affected where we are. The tropical storm season in the Arabian Sea has already begun and will continue through late November. We are sailing only a few hundred miles past this region and may well expect some rough weather as we approach the Gulf of Aden. Right now, as if sensing our desperation, the wind has taken pity on Aphrodite and has stayed with us.

Seychelles to Djibouti: October 14th, 1994

02° 47.8’ N / 49° 47.3’ E

I feel as though I have changed my life by the direction I am heading in and in doing so have become somebody new. From the moment I first stepped on the deck of Aphrodite I began the transformation. Now, one hundred days later I feel like a different man, each day brings new experiences, and with each experience comes change. The experiences we have in our life affect our actions, as our actions define who we are, experiences have the power to change who we are. The power of a single thought that becomes a decision can have a profound influence on your life, it can change everything you have ever believed to be true.

In one hundred days we have sailed over seven thousand miles because of a single decision made by each of us. One hundred days ago I wouldn’t have felt confident in navigating my way out of Sydney Harbor. Today I have just finished plotting our route up the Red Sea. Using six different charts I have managed to find our way up to the entrance of the Suez Canal.

Seychelles to Djibouti: October 15th, 1994

04° 29.4’ N / 50° 05.4’ E

The temperature inside the cabin is over a hundred degrees. Barry, the barometer, is holding steady in the fine weather region and the skies are completely clear of clouds. We’re motoring up the coast of Kenya, about a hundred miles off to our port side but far from sight. The horizon to the west is hazy and out of focus. The sands from the deserts of Africa are blown up to thirty miles off the dry coast. The winds are known as the Kharif and can sometimes reach gale force during the night. We only have a single knot of current with us but it should strengthen as we head further north.

Seychelles to Djibouti: October 18th, 1994

12° 07.8’ N / 50° 51.3’ E

Today we have rounded The Horn and are heading west to Djibouti, four hundred and fifty miles away at the far end of the gulf.

We’re only eight miles off the coast of Africa and have officially left the Indian Ocean. The full moon tonight is high in the starry sky and bright enough to read and write by. Its reflection is dancing off the little waves, covering the surface of water in glitter. We are sailing along the cliffs of Somalia along the southern edge of the Gulf. To the north, Yemen is in conflict, we were advised by one of the freighters to steer clear of this country. The unsettled relationship between North and South Yemen has remained high since the two united in 1990. Aden is the former capital of South Yemen and a more convenient stop for yachts heading north up the Red Sea. The harbor offers very little comfort for cruising yachts and formalities are said to be complicated. Djibouti, although not quite as convenient offers a safer anchorage and has better facilities, we should arrive there in under a week.

Seychelles to Djibouti: October 23rd, 1994

11° 36.3’ N / 43° 12.1’ E

It’s Sunday afternoon, the 23rd of October, we are in the Gulf of Tadjoura and can clearly see the port of Djibouti ahead. Unlike the tropical islands in the Indian Ocean, Djibouti is a working port with heavy traffic and dirty waters. Two massive cranes stand erect in the harbor, ready to unload more cargo from the ships that endlessly steam down from Port Suez. There are two giant freighters waiting patiently for their heavy loads to be unburdened from their backs. Boats of different shapes and sizes are anchored around the large harbor, some are rotting at their anchorage with gaping wounds in their sides, barely managing to stay afloat, while others like the two French warships sit menacingly at the entrance of the harbor with their guns uncovered. Thick black smoke is billowing up from the eastern end of the port and scaring the blue sky, everything looks dirty and oily, it’s not a pretty sight.

The country of Djibouti is little more than a port in the Tadjoura Gulf. The population of around 580,000 are mainly Afars and Issas, although there are also a large percentage of refugees from the neighboring countries of Ethiopia and Somalia. Before Djibouti was occupied by the French it was little more than grazing land for nomadic tribes. In 1862 the French acquired the rights to settle in Djibouti to counter the presence of the British in Aden. In 1888 construction of the port and town began along with the Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway that provides Ethiopia with an outlet to the sea. The French eventually gave Djibouti independence on June 26th, 1977 due to increasing acts of terrorism by the Issas. Arabic is the official language but French is widely spoken as France still provides aid to the country and has maintained a military presence due to its agreement with Djibouti.

We have spoken to the Capitainerie on channel twelve and received our instructions. The master of the vessel is required to motor over to immigration in the commercial harbor to present passports and fill out the papers. Peter has given me this title and seems to be more relaxed knowing that he will not be responsible for filling out the forms and dealing with the authorities. I think he is intimidated by all the paper work and would much rather stay on the boat and drink beer instead.

NOTE: We stayed in Djibouti only three days, just long enough to resupply. We also purchased five, 10 gallon drums to store additional diesel to help us power through the head winds of the northern Red Sea.

Djibouti to Suez Canal: October 26th, 1994

12° 30.9’ N / 43° 12.2’ E

With our new Djibouti courtesy flag flying from the spreader we have set out for the Gates of Sorrow six days behind schedule but ready for the Red Sea. Peter is the happiest I have seen him for weeks as he has stocked up on cigarettes and is now ready to battle the northerly winds. “How many cartons did you buy there Peter?” I asked. “Oh, about twenty-two. At eight dollars a carton you can’t go wrong!” Peter added as he sucked another one down. “That’s a bargain!” Lewis said with a grin. “It’s almost enough to make you want to start smoking,eh Lou?” I said. “I don’t know about that!” “I won’t be able to give up for a while anyway.” Peter said with a cough.

We have taken two cartons away from Peter’s stash and stored them for “backseesh.” We have read that the authorities through the Suez Canal respond favorably to packets of cigarettes, Marlboro are the preferred flavor. The right “donation” will help to ensure a quick and easy passage, without them your trip could be mysteriously delayed. Cigarettes are like a currency and the bigger the ship the larger the payment. The freighters that pass through the Suez reportedly pay by the ton. The larger freighters weighing in at three hundred thousand tons pay $4 -$5 per ton and dozens of cartons of Marlboro.

I’ve been studying the chart and the narrow passage we will be taking into the Red Sea. It’s a little intimidating. Tiny islands bridge the twenty mile gap between Yemen and Djibouti and each of them must be passed on the correct side and at a safe distance.Some yachts have reported being shot at because the currents brought them too close to restricted areas. Due to the heavy traffic, a separation zone is in operation and divides northbound from southbound. Northbound vessels must pass to the starboard side, yet maintain a safe distance from the restricted islands and the waters surrounding them.

We will pass through the Gates of Sorrow around dawn tomorrow. It is important that we clear the headland of Ras Bir by at least ten miles and sail east past the Musha Islands. It will be extremely dangerous to attempt the passage to the west as rebels have been known to molest vessels that pass too close to the Djibouti coastline. When we reach the Gates of Sorrow we must keep a safe distance west of Perim Island as yachts have been used for target practice if they venture too close. Once we have cleared the entrance we will sail toward Tair Island then continue north to the Hanish and Zubair Islands, which belong to Yemen and are en route to Jabal. If the weather is not in our favor, anchoring at these islands is tolerated but landing is prohibited. If the wind and currents are with us we will press on.

Djibouti to Suez Canal: October 27th, 1994

12° 47.9’ N / 43° 16.9’ E

We passed through the Gates of Sorrow in the early hours of the morning and in doing so have begun our journey up the Red Sea. We’re howling along averaging nine knots over ground, the wind is steady at twenty-four knots from the northeast and the current is in our favor at three knots. It’s 0800 and heavy traffic has been continuously steaming down from the north all night. So far we have spotted one oil rig, twenty freighters and we have just been joined by a battleship. Needless to say with so much company during the night I was unable to sleep and am in dire need of a power nap.

The French battleship has just cleared our stern by no more than half a mile. To our starboard side is Perim Island. If they start shooting at us at least we’ll have the support of the French on our side. The missile launchers and turret guns mounted onto the cold grey deck are uncovered and pointing menacingly to the north. Its grey streamlined body is slicing through the waves at twenty-five knots like the dorsal fin of a shark.

It is recommended for yachts sailing the Red Sea that they listen to the international news. If any disputes should occur between neighboring or divided countries, tourists are advised to steer well clear of the trouble until it has been resolved. The Gulf War in 1991 is a reminder that at any time, and seemingly out of nowhere disruptions can occur and the best place to be is as far away as possible.

Djibouti to Suez Canal: October 28th, 1994

14° 59.5’ N / 42° 10.0’ E

Still making unbelievable time, the wind is blowing from the southwest at twenty knots and we have been surfing the waves that sweep up behind us. Last night we hit thirteen knots as we slid down the face of one. If this keeps up we will make up the six days we are behind and arrive in Port Suez right on time. Zubair Island is on our starboard side, there looks to be no safe anchorage as the giant rock rises vertically out of the sea. We should expect a little turbulence as we pass it, the wind will blow around the island causing a disturbance.

Djibouti to Suez Canal: October 29th, 1994

17° 59.4’ N / 39° 27.5’ E

We’re two hundred miles from Sudan and have left the main shipping lanes and are sailing closer to the western coast. We no longer have to contend with the giant freighters but will need to keep a closer eye on the charts and our position. The reef up the western side of the Red Sea has not been accurately documented and the charts have warnings on them indicating that there may be an error of up to two miles. The three of us have spent the day outside under the shade of the mainsail. The cabin has been so humid that I slept outside after my watch last night. The wind is still blowing from the southwest, which we are all thankful for.

Some wise guy has been entertaining us and all the other boats up the Red Sea by playing Whitney Houston and Brian Adams on the VHF emergency channel sixteen. Over supper we listened to “Run to You” by Bryan Adams and “I Will Always Love You” by Whitney Houston from the movie Bodyguard. Whoever it was has no respect for radio etiquette.

In between tracks the “DJ” ignored the requests to, “Get the f--k off the emergency channel!” and quite happily carried on a conversation with himself in Arabic. With so much chatter it’ll be impossible to hear the cries of someone in danger or requesting assistance.

Djibouti to Suez Canal: October 31st, 1994

20° 23.0’ N / 37° 58.0’ E

I was awakened suddenly at 0200 this morning when my head smacked into the ceiling of the cabin. During the night the wind and swell had picked up into a storm and we were sailing right into it. The nose of Aphrodite was pitching up and down so severely I spent more time in the air than on my bunk. When we fell off the really big waves I was slammed up against the ceiling. My sheets, pillows and cushions are all completely drenched. Each time we took a nose dive the bow scooped up water and shot it down the length of deck toward the stern. My hatch, I have discovered, is not watertight. Lewis and Peter were sitting in the cockpit with harnesses attached to the helm. After I moved all my drenched gear from the bow cabin and threw the cushions and sheets around the saloon to dry them out I put on my harness and staggered up to the cockpit to join the party.

The wind is peaking at forty-six knots and howling northwest across the ocean from Egypt. The waves are crashing into the bow as we met them at eight knots, sending spray into the air. Each time we duck under the splash deck to avoid a drenching. The sails are reefed right down to little pieces of cloth and Aphrodite was holding true.

The morning after! It’s 0900, the sun is shining making everything seem more bearable. Now that there is enough light, Peter has the camcorder out and is documenting our first storm. Because of the conditions, it’s too wet and rough to sit up on the deck so we’re all sitting inside the cockpit enjoying the ride. We’ve been getting on much better as a team since we left Djibouti, the differences are still apparent but the weather is keeping us occupied. The wind has been slowly swinging back around to the southwest now that the sun is up and has died down a little. The cabin area looks like we’ve been ransacked; cushions, pillows, sheets, towels, cloths and books are littered around the small space making it almost impossible to reach the bow cabin that is drying out. It’s far too rough and windy to peg anything to the railing.

We have passed the halfway mark of the Red Sea and have sailed right past Port Sudan. To pull over now for a rest would be a waste of good wind and dangerous heading into the reefs. As George told me back in Cocos, “When in doubt, stay out!” We have only been at sea for five days and would much rather have a couple more days to see Cairo than in Port Sudan. Once we’re at the entrance of the Suez Canal we’ll know that the worst of it is over and we can relax a little.

Djibouti to Suez Canal: November 3rd, 1994

23° 31.5’ N / 36° 32.7’ E

We’re only thirty miles from the Egyptian coast, the wind has died down a little and is now blowing steadily from the northeast. We’re motoring to try and make as much northerly as we can while the wind is light. We only have two hundred miles to the Gulf of the Suez and then another one hundred and eighty to the entrance of the Canal.

There’s lots of debris floating in the water, presumably washing down from the Suez. Planks of wood, metal drums and hundreds of plastic bottles. The river of trash we saw in the Indian Ocean sailing to the Seychelles probably originated from the Suez and washed down the Red Sea into the Gulf of Aden.

The whole world is hot. The mercury inside the cabin is pushing one hundred degrees, outside the cabin it’s ninety-seven degrees and the water temperature is eighty-nine degrees. If my feet were not as hardened as they are, I would find it very difficult to walk around on the scorching deck. After four months with no shoes however, my soles are as tough as leather.

Djibouti to Suez Canal: November 4th, 1994

25° 01.7’ N / 34° 31.5’ E

It is a humbling feeling to watch the dark clouds roll in from the horizon in every direction, knowing that a storm is coming and that you can do nothing about it. At 1800 hours the sky became swollen with clouds that closed in around us. These storms only seem to come at night, they are so predictable you can almost set your watch by them. The last four nights have welcomed us the same way but last night was the one that made us all stay up.

The peaceful day ended at 2100 hours when the sky became saturated with black clouds and the first noise of thunder rumbled across the sky as the sun dropped into the horizon. The thunder was so deep, I felt the vibration in my stomach. As the night grew darker the lightning took over the blackness and filled the sky with light. Some spread across the base of the clouds, like a network of veins that never reached the ground. Other bolts shot out of the clouds straight to earth with a terrifying crackle that followed seconds later and echoed across the night.

Djibouti to Suez Canal: November 6th, 1994

27° 37.4’ N / 34° 01.7’ E

We have officially left the Red Sea and entered the Gulf of the Suez through the Straights of Gûbal. Although Port Suez is only one hundred and eighty miles away we have the current, twenty-seven knots of wind and six feet of swell against us. The engine is hammering at 1800 RPM but we are only barely managing one nautical mile an hour. At this rate it’ll take us another week to reach the top of the gulf!

It’s 1700 hours, the traffic is heavy now that we are in the narrower passage. We’re only one mile southwest of the Morgan oil field and as the sunlight fades to the west, flames from the working rigs to the east mark the sky as they continuously burn off the excess oil that’s pumped out from below the ocean bed. Tiny plumes of smoke rise into the night air from the twitching flames that light the ocean around them like street lamps down a dark alley.

Helicopters are flying back and forth from oil rig to oil rig like bees pollinating flowers, cargo vessels are steadily steaming past us in the center of the gulf, it’s been a long day but I have a feeling it’ll be an even longer night. Many of the rigs surrounding us are no longer in use and do not have lights to warn boats of their position. The huge platforms sit patiently in the ocean waiting for someone to pass too close and get snagged in the many cables and supports. We’re hoping tonight will not bring a storm as we have no room to maneuver. The sky is still clear and the first stars are beginning to show themselves.

Djibouti to Suez Canal: November 7th, 1994

28° 56.6’ N / 32° 49.5’ E

Today marks the end of our fourth month since we left Sydney. I can hardly remember what my life was like before this journey, the life I know now is my reality and it’s difficult to imagine living any other way. We all miss our families and loved ones beyond belief, the hardest part of this voyage is being away from the ones I love. Not knowing where or how they are is worse than anything else I have endured so far. I have not spoken to Catherine since the Seychelles, I write to her each day and have over twenty pages, front and back to mail from the Suez. I need to hear the sound of her voice, I want to tell her that I love her.

I’m ready to begin the next chapter of my life, I’ve had so much time to think about what I want, I’m all wound up and ready to be let loose. I have so much that I want to achieve, so much that I have to do that I’m getting impatient. I know I will miss these days when it is all over but right now I feel as though I have had enough. We are all fidgety and ready to leave. At 0800 I put the jib up and gave the engine a rest, we have been sailing ever since. The wind was blowing at twenty-seven knots right on our nose, motoring was just burning diesel and barely managing to keep us stationary. Although there is heavy traffic on the eastern side with freighters steaming past us at twenty knots, and oil rigs and platforms on the western side, I am actually enjoying myself. The auto pilot has been turned off and we are sailing! Peter and I are taking turns to man the helm as we tack back and forth across the gulf timing our path and heading to miss the giant container ships. It’s as though we’re crossing a busy highway with speeding cars passing us on every side.

Although the journey is almost over, we still have another three to four weeks left to go. I get the feeling from Lewis and Peter that they feel the same way. Five months ago we couldn’t wait for the journey to begin, some of us had waited a year, others a life time. Now we’re almost as eager for the journey to end. The last five days have been hard work, the constant night storms and head winds have drained our bodies of energy. We all need a rest and a sound night of sleep before we make the final ascent into Port Suez. There is a secluded bay a few hours away on the Egyptian coast. We will anchor there tonight, rest up and navigate the last fifty-five miles to Port Suez tomorrow. We headed toward the sinking sun, sailing along the shimmering golden path reflected in the water that led us into the tiny bay of Marsa Thelemet. Surrounded by hills and desert, the golden sand is being blown by the thirty knot Khamsin wind. The only signs of life are a few dried out mud huts huddled along the shoreline that seem to be abandoned. The hills are sheltering us, the holding is sand and the water calm, never before have I looked forward to sleep more than now. We will leave tomorrow at 1200 after a nice lay-in and a large breakfast.

Port Suez: November 9th, 1994

As the first sign of daylight marked the sky, the mouth to the Suez Canal showed itself. Dozens of freighters were anchored around the entrance waiting for their turn to go through to the Mediterranean. We called the Prince of the Red Sea on channel twelve to announce our arrival and to arrange a pilot to come and guide us in to the yacht club. He told us that he would be sending his son out to welcome us to Egypt. Heebi would be a few hours so we had time to clean the boat and make ourselves a little more presentable after not showering properly for almost a week.

Heebi’s family has been working the canal since it was first opened in 1869. His grandfather was the Great Prince of the Red Sea, the title has been past down through the generations. As Heebi shared his stories with us and the history of his family and the Suez Canal, he expertly steered Peter’s precious Aphrodite with one hand, while appearing to try and pass the other boats and buoys in the harbor as close as possible. When he lit up a cigarette Heebi continued to steer with his foot.

The Suez Canal took ten years to dig, one and a half million Egyptian workers took part in the backbreaking project, over one hundred and twenty thousand workers lost their lives working in the canal. On November 17, 1869 the canal was opened, joining the Mediterranean Sea with the Red Sea for the first time and halving the distance for ships taking cargo from Europe to the Far East. The canal has been closed twice, once in 1956 for a year and for a second time from 1967 to 1975 following the Arab-Israeli war. The canal reopened in 1975 once cleared of wreckage and mines, and was enlarged in 1976 to 1980 for the growing number of tankers, giant cargo vessels and the ever-increasing number of ships using the canal.

Port Suez: November 12th, 1994

Our pilot joined us this morning at the ungodly hour of 0730, ready to hold our hand and help us navigate the sixty or so miles of canal to Lake Timsah. We will anchor there this afternoon in the far northwest corner by Ismalia and wait until tomorrow morning when hopefully, not as early, our new pilot will join us and guide us through the second half of the canal to Port Said and the Mediterranean Sea.