|

View past entries by month and year:

|

|

|

|

Charleston, South Carolina

09:43 hrs - October 20th, 2024

Nothing to Spare in the ICW |

For ten days we have toured two hundred and thirty nine miles of the northern ICW, or Intracoastal Waterway - a network of connected rivers, estuaries, sounds and manmade canals that cut through an appealing slice of Americana that is mostly hidden from the highways.

We've cruised this portion of the ICW on Dream Time and found it provides a charming contrast to our open ocean passages and the turquoise-saturated tropics. Besides, hurricane Milton was still causing mischief around Cape Hatteras - a shoal riddled surf swept protrusion on the coastline that's claimed so many ships it's infamously known as the Graveyard of the Atlantic - so chugging peacefully along the ICW provided an attractive alternative. But unfortunately with Mana it was not quite the carefree river cruise we had experienced in the past.

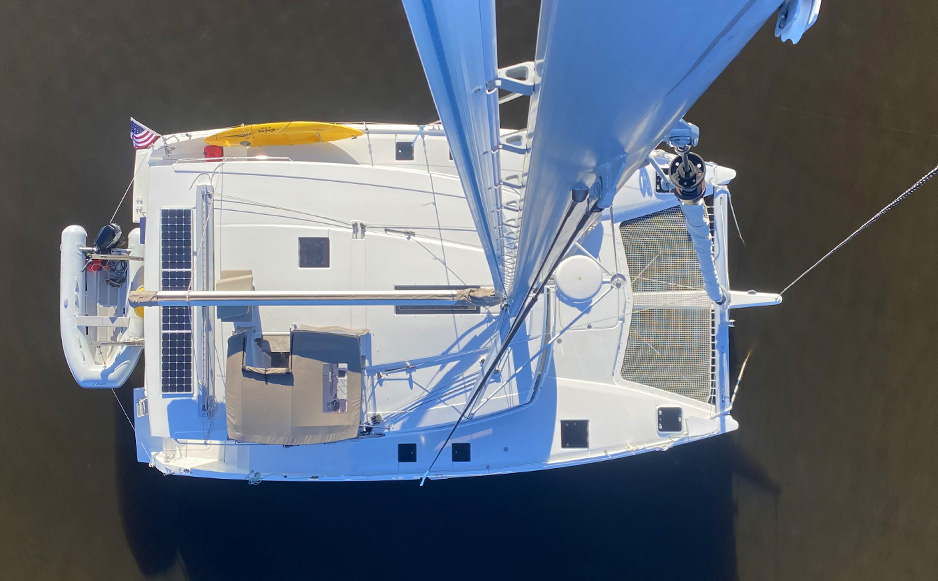

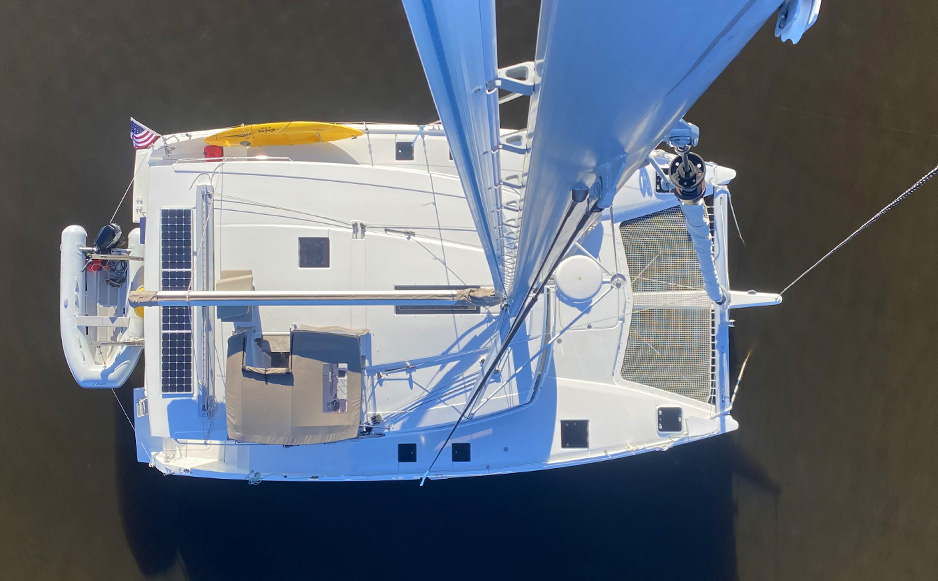

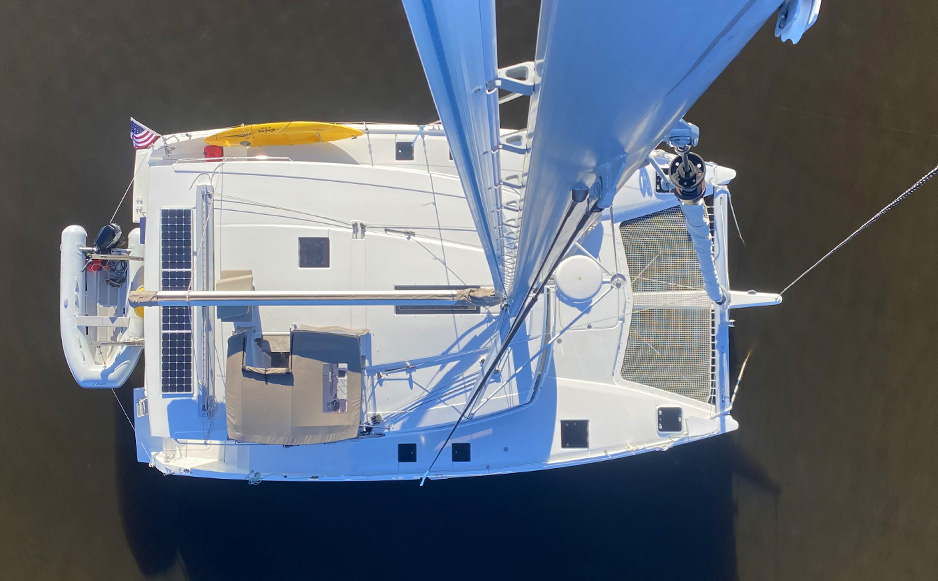

You see, while Mana is the same length and even the same weight as Dream Time her beam is ten feet wider and she carries a mast a full ten feet taller off the waterline. The French designers of this particular catamaran, noting the large market of East Coast American cruisers wishing to access the ICW, proudly proclaimed when unveiling their creation that she was "ICW friendly" with a mast that stands sixty-three feet, three inches.

Now in theory they did a marvelous job accommodating the requests of this cruising community, after-all the official height of a fixed bridge on the ICW, as determined by the Army Corp of Engineers, is sixty-five feet. But what the Fountaine Pajot designers kept quiet (or perhaps mention only in legal disclaimer text too small to find in the sales brochure) is the collection of instruments installed on top of the sixty-three foot three inch mast - a tricolor light, for example, that adds eight inches; an anemometer (the little spinning cups that measure wind speed) which adds a whopping twelve inches to the masthead; and radio antennas, another two to three feet. You see where I’m going with this, add-up all these appendages and your air draft soars to well past the acceptable margin.

When we purchased Mana she carried two generous three foot rigid antennas atop her mast, making her too lofty for the ICW, so in preparation we replaced the rigid antennas with a flexible whip variety and just last week, before departing Norfolk at the southern end of the Chesapeake Bay to enter Mile Marker 0 of the ICW, Catherine sent me up the mast to remove the anemometer and tricolor light. We stripped our masthead down to a few plastic mounts (measuring three inches above the masthead) and, curious to know just how close would actually be to hitting the underside of the bridges, I cable-tied a sacrificial eight inch white plastic stick to the masthead fashioned from an old coat hanger.

So chug south we did with a total of sixty-three feet six inches of unsacrificial air space and we cleared the first sixty-five foot bridge, albeit very slowly (less than a knot of boat speed) with just the very tips of our two-foot whip antennas tickling the rows of bridge trusses, jiggling and swaying in a jolly manner that did not reflect the feelings far below on deck. Our sacrificial stick remained unmolested so we deduced the top of our mast cleared by approximately two feet and with a deep sigh of relief we continued south confident we had literally taken all the right measures. But our relief was short lived as after transiting Great Bridge Lock we entered a portion of the ICW not influenced by diurnal tides, but rather a region where rainfall and wind dictate water levels that regularly flood river banks, close roads and can reduce bridge clearance by up to four feet.

"Why don’t you just read the bridge tide boards before you proceed?" I hear you tut. Well, that would be a wonderful idea except: 1, not every bridge on the ICW displays these useful boards that show, by the water level, what the bridge clearance is above; 2, some boards are so horribly stained you can’t read the numbers leaving you, during an intensely stressful time and wide-eyed on the edge of panic, attempting to hazard a guess; or 3, either due to bridge subsidence or an engineer with a wicked sense of humor, are estimated to be six to twelve inches off the measured mark.

Three bridges on our stretch of the ICW between Norfolk and Beaufort had captured my attention: the Pungo Ferry Bridge at mile marker 28.3, that many cruisers claim offers only sixty-four feet and, to keep things interesting, only displays tide boards on the south side of the bridge (we were inconveniently approaching from the north); the Fairfield Bridge at mile marker 113.9 also rumored to be sixty-four feet according to unfortunate captains who suddenly found themselves with no wind measurements at the helm; and the Wilkerson Bridge, mile marker 125.9 which as one popular cruising guide officially warns, "Has one foot less clearance than the Army Corps of Engineers authorized vertical clearance."

When we passed under the Pungo Ferry Bridge, rather than jiggle and wobble in a jovial playful fashion our whip antennas performed alarming downward dogs when meeting each truss before sharply twanging back into their upright positions. We estimated by the extreme angle of their forced limbo that the air clearance was just sixty-four feet, or six inches above our non-sacrificial components. It should be noted, lest you consider us entirely reckless, that we had only proceeded under this bridge as Dream Time, yes, our trusty old vessel under the command of her new owner, Nick, had texted photos of the south side tide boards showing sixty-four feet during an earlier transit. It was close, but our sacrificial eight inch rod stood proud so it seemed the boards were accurate.

We continued south in brisk northerly wind, sailing across the Albemarle Sound before anchoring for the night in a scenic bend of the Alligator River surrounded by towering loblolly pine, crab pots and bird song. This would have been a peaceful anchorage if not for the growing unease of the two bridges that lay ahead. Seven miles down the Alligator and Pungo River Canal was the first, Fairfield Bridge, but the morning of our departure confidence soured when a useful marker at the northern end of the canal which gives mariners a convenient head-up on what to expect seven miles further south, displayed a clear number "1" - an indication, we had learned, that the bridge would allow sixty-four feet. Again, measurements proved to be accurate as we passed a little over an hour later with our sacrificial rod remaining in the full upright position. We continued ten miles along confident we would transit the third and final troublesome bridge without incident. But as we approached the notorious Wilkerson Bridge, with the tide boards coming into clear view, we were dismayed to observe the "64" mark sloshing half under water indicating approximate air clearance at a meager sixty-three and a half feet - the exact height of our unsacrificial air space.

When I measured the mounting hardware at the top of the mast in Norfolk I had generously rounded up by half an inch. So, to proceed or not to proceed? That was the question. With no anchorages in the canal aborting would require a three hour detour back to Alligator River, an unappealing thought when freedom was less than twenty feet away. But of course judging the height of these bridges from the deck is an impossible pursuit, particularly when concerned with mere inches. So the decision was made to proceed, at a speed so slow it would not register movement through the water, Catherine clutching binoculars to peer at the masthead from the bow while I gripped the wheel craning my neck to ensure I at least avoided hitting the light that dangled a foot below the bridge.

Contact with the first truss confirmed this would be our closest transit to date. The antennas hit once again, about two thirds down their length, scraping along the bottom of the bridge before springing back into their upright positions in the recess that offered an all too brief respite between trusses. Judging by the gasps echoing from Dream Time keenly observing safely from the south side, the next three trusses each offered consecutively less air space than the first. The fifth truss struck the middle of our sacrificial rod - we were now under sixty three feet eight inches and had just two inches of sacrificial airspace remaining.

To briefly put these margins into perspective, a luxury we were not able to fully reflect on at the time, relative to Mana’s total sixty-three foot six inch air draft, we were now reduced to the last of her 0.25% clearance, equivalent to about the length of the prongs on your dinner fork for a mast the height of a five story building.

One final truss remained between us and the sweet uninterrupted freedom of blue sky beyond. The sixth and final truss was lower still, and video taken from Dream Time shows a degree of precision typically reserved for, say, the docking of a craft at the International Space Station. Our sacrificial rod was swept away, and we watched our flexible antennas contort to the very margins of their tolerance followed by a metallic clatter as debris fell to the deck. We had made it. But at what cost?

An hour later Mana was anchored in Pungo Creek and I was winched aloft, bracing myself for the gnarly mess of sheared tricolor wiring and a cracked anemometer bracket I was sure awaited, and eager to learn exactly where the two inch razor sharp shard of aluminum that we found on our deck had come from. My discovery at the top of our mast was a shock. Perched on the bosuns chair sixty feet above the water I found our masthead, along with all the mounting brackets and wiring, in perfect condition with nary a scratch. Even the Ziploc bag and blue masking tape I had installed in Norfolk was in tact. Echoes of my jubilant cheers could be heard all across North Carolina.

Our first ICW transit on Mana, a detour that should have been a pleasantly relaxing scenic river cruise, was as anxiety riddled as navigating our first labyrinth of uncharted shallow reefs; weathered a tropical storm with double anchors in Belize; or even when surfing thirty foot waves in the South Pacific on a return passage to Tahiti from New Zealand. Would we do it again? Well, we don't consider ourselves reckless, we're conservative cruisers and believe that's how we were able to circle the world with Dream Time, over 50,000 nautical miles in fourteen years, without serious incident. But at the same time we don’t allow our fear to restrict our desired movement, if we did we would likely never have gone cruising in the first place. What we do, however, is take every reasonable measure possible to prepare for a challenging situation to help ensure the best outcome.

So yes, I think perhaps we would do it again, approaching from the south where the luxury of convenient anchorages allows for the daily monitoring of tide boards or, like many owners with lofty rigs wishing to make portions of the ICW part of their annual migration, only after trimming a few feet from the top of the mast.

Oh, and the aluminum shard that fell to our deck. We can only deduce that our antennas or sacrificial stick had dislodged this relic left behind from a previous vessel that had scraped through with literally nothing left to spare, leaving us with an unsettling souvenir of just how close we had come.

|

|

|

Cape Lookout, North Carolina

09:36 hrs - October 14th, 2024

A Different Language |

For twenty four years we sailed Dream Time, and she spoke to us - her creaking, knocking, groaning and whirling - every noise meant something, and we knew them all. Like, “Hey buddy, ease that main sheet a little”, or “I’m enjoying this, what a marvelous sail!”

Most of her noises, the sound of teak cabinetry flexing on a hard passage to New Zealand, the stretching of a snubber with kite surfing trades building across the Tuamotus, or the harmonic whistling of following winds blowing through the holes in our adjustable solar panel frame, they were all familiar to us, and many intensely comforting, like the crackling of a wood fire on a cold winter’s night. You see, we knew we were safe with Dream Time, because she told us so. Occasionally, rarely, she would scream at us, yell for our attention with a sudden jarring crack followed by an uncertain murmur when her forestay parted, or the deep low knocking when our chain hook straitened in seventy knots during an intense Mediterranean storm and, link by link, our anchor rode tore through the windlass. Yes, Dream Time spoke to us and we understood what she was saying.

But Mana is our new boat, and an entirely new style of boat, so her noises, her language, are mostly unfamiliar to us. We’re still figuring out what sounds are OK, and which require careful or even immediate attention. And of course she is French, so it will likely take some time to fully understand what she is saying to us. But we are already really enjoying the conversation. Merci mon amie! |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Glen Cove, New York

18:44 hrs - October 6th, 2024

Seventeen Years |

In June of 2007 we moved out of our Long Beach NY apartment and onto Dream Time to see what life could be like outside the edges of our familiar land life, and after a satisfying 14 years of circumnavigating adventures we moved back to Long Beach, with the sincere, but untested intention of settling back into comfortable landlubber living.

But as many folk will not be surprised to hear, in June of 2024, we moved out of our NY apartment once again, and moved onto our beautiful new catamaran home, Mana.

Life in NY was rich, full and deeply satisfying. Our old familiar NY friendships were reignited and new friendships blossomed, but quietly in the background of everything, was this faint but ever present and steady understanding that I was supposed to be somewhere else.

From time to time I would think about it and try to understand what I was feeling and why, and finally came to realize that I just wanted to be back on the water, I wanted to be back on a boat again, and luckily, with some gentle persuasion, Neville agreed.

So now seventeen years later we are leaving Glen Cove, once again to sail down the East River, to the Statue of Liberty, to Manhattan’s much changed skyline, to begin perhaps another circumnavigation?

Anyone who has made the transition from monohull to catamaran will appreciate the wonderful advantages of all the additional living space and comfort that catamaran living affords, but the surprise, to me at least, was the steep learning curve. Catamaran sailing dynamics and loads are so completely different from a traditional monohull, and learning how to sail Mana with the full understanding of what weather, wind and more importantly what a large amount of sea can do was intimidating, but with the advantage of some hard earned experience and somewhat advanced years, we are learning and absorbing every detail, and Mana is teaching us something new every day.

But the first leg of our journey south on Mana showed us that we still had more to learn.

The first challenge was delivered as we were getting ready to leave New York. Just before we left we found out that NYC was hosting the 79th session of the UN General Assembly, which meant that the East River, our route out of NY, was going to be closed to marine traffic starting now… for a week! But hey, no problem, it would re-open after 5pm each day and as luck would have it, that timing worked for us. So great, we’re off. But next, as we reach the Whitestone Bridge suddenly NYPD and FDNY boats sped past us emergency lights flashing, towards a small power boat near the bridge. Then we started to see police lights on the road too and began hearing radio traffic on 16. Coast guard is reporting a “person in the water”. Someone had fallen from the boat into the dark water by the bridge, and to the shock of the people left on the boat, and to us, the person, not wearing a life jacket, had fallen and not resurfaced. In the blink of an eye a sunny Sunday outing on a friends boat had changed lives. NYPD divers were next to arrive and as we listened in silence on 16, they discussed the speed of the current and where that would indicate their underwater search would begin. Stunned we realized there wasn't anything we could do to help. And were instantly reminded of why we take the responsibility for each other’s safety, so seriously.

Then next, just as we are reaching the point of no return, at the unapologetically named ‘Hell Gate’ the ominous point where turning around in that fast current becomes dangerous or impossible because of turbulent rushing water, we start hearing that our route the, currently closed portion of the east river which was scheduled to open at 5pm was now to remain closed till 10pm!?! So we now suddenly have to go to Plan B, the Roosevelt Bridge route, which is not ideal, and normally closed, opens conveniently for “on demand” requests, but inconveniently requires 2 hours notice! And we will be there in 45 minutes…

But I’m married to a genius, and the genius anticipated the possibility of a glitch and called the bridge this morning to request a 6pm opening. Just in case...

So now all we have to do is get past Hell Gate and the frequent dangerous and unpredictable whirlpools that 4 converging waterways produce and if the East River gods are with us, hopefully get to the bridge as it opens… |

|

The Dawn of a New Journey

September 23, 2024

New York

Our voyage began with Dream Time and lasted twenty-four years, including a fourteen year voyage around the world, and it was a remarkable adventure. But in the Spring of 2024 Dream Time welcomed a new owner, an American we first met in Belize over sixteen years ago at the very beginning of our world journey (read 2008 blog). A man who would become our friend and who would later help us transit Dream Time through the Panama Canal into the Pacific and sail with us in Tonga and Tahiti. It seems they were destined to be together. So while it may be the end of our magnificent voyage with Dream Time, she is in caring and familiar hands, and we are grateful for that.

But our adventures are not over, indeed they have begun anew! We have purchased a Fountaine Pajot Lucia, a forty-foot sailing catamaran that we have named Mana. We first heard of mana (maa-nuh) in the remote tropical islands of the South Pacific. It is a word rooted in Polynesian and Oceanic cultures by an intrepid people who, over two thousand years ago, without charts or any knowledge of what lay over the distant horizon, boldly sailed their double-hulled canoes from Southeast Asia across the world's largest ocean. They believe mana is an energy that permeates the universe and is a cultivation or possession of power. It is an intentional force that a person, place, and even an object, like a Fountaine Pajot catamaran, can possess.

We have spent the last three months upgrading Mana and have just raised sail from New York for our first passage south where Mana will receive her second-round of upgrades and then, possibly, a little winter cruising to test her new gear in the Bahamas. Our experiences and adventures will once again be shared on the pages of zeroXTE. It will likely take us a few weeks, or months, to fully update the site with vessel details, but stay tuned, like Dream Time's five-year voyage that became fourteen, we shall get there in the end. |

|

|